Steel industry is in hell and the pain shows no sign of letting up

Crisis in UK steel may continue for years, says analyst in comprehensive note highlighting China's massive over-capacity

Britain’s struggling steelmakers face years of “hell”, according to experts, with the crisis in the industry showing no signs of letting up.

Brokerage Jefferies said the past year “has felt like hell” across the global steel industry and warned it is unlikely there will be any short to medium-term relief from the pressures that have claimed thousands of British jobs.

In a comprehensive 203-page examination of the industry, analyst Seth Rosenfeld said: “Dante wrote ‘The path to paradise begins in hell’ but we must determine which level of hell we are at to judge how close we are to the end.

“With Chinese demand contracting, trade policy providing limited salvation and ‘bull case’ restructuring bringing years of volatility, we have far to go before reaching the ninth circle.”

China has a huge steel over-capacity as a result of the country’s economic slowdown, meaning it dumps commodity output abroad. Having peaked in 2013, China’s demand for steel has declined 8pc since 2013, according to Jefferies, with the brokerage forecasting a further 2pc drop this year.

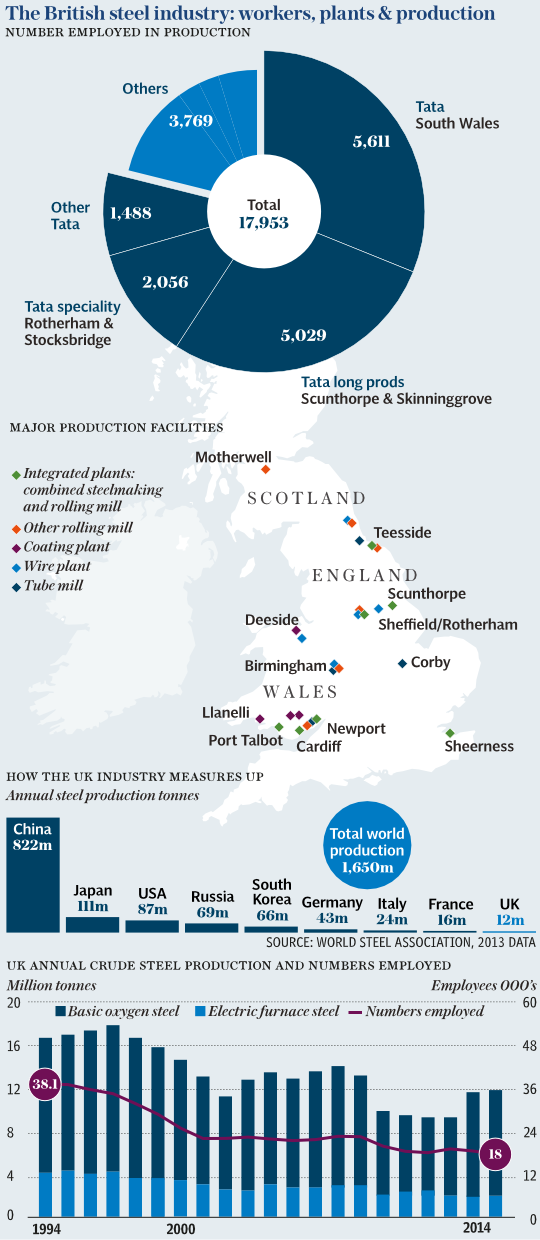

However, production outside the country – the world’s largest steelmaking nation, producing about half of the 1.6bn tonne total - has fallen only 4pc in the past two years, though exports have surged 79pc, acting as a “release valve”.

Mr Rosenfeld added: “China has roughly 360m tonnes per annum of excess steelmaking capacity, reflecting expected 2016 production of 794m tonnes versus capacity of about 1.15bn tonnes.”

The imbalance means China needs to shed 230m tonnes of production, according to Jefferies, but is unlikely to do this because of fears of the destabilising impact it could have on the country, despite the Beijing government’s pledges to deal with the issue.

“Realistically, the implementation of policy-led restructuring efforts may continue to be held back by the 3m direct employees in the steel industry, and many times more in secondary industries,” said Mr Rosenfeld.

He added that Chinese steel companies have debts of $520bn, mainly held by Beijing-backed banks, noting: “Do Chinese banks and policymakers have the stomach to manage an impending default crisis that will naturally come alongside steel plant closures?”

Mr Rosenfeld said the US and European steel industry would continue to feel the shockwaves from this global overcapacity until China deals with its problems, raising the prospect of further consolidation.

European steelmakers are more exposed than those in the US, having been slower to react to changing demand than their transatlantic peers.

More than 4,000 redundancies have been announced in the UK steel industry in the past year – mainly at Tata plants and at SSI’s Redcar site – and the worsening crisis could force the EU to introduce measures to protect the industry from Chinese imports, according to Mr Rosenfeld.

“SSI’s decision to close its UK steelmaking facilities – about 2pc of EU capacity - may provide a jolt to policymakers that more needs to be done to protect the local industry or more closures will inevitably come,” the analyst said.

British trade body UK Steel has led a campaign for action to protect jobs in the industry, recently securing a rebate on green levies on energy bills that made this country one of the most expensive to operate for steelmakers. It has called for the EU to introduce import tariffs to discourage China from flooding European markets with cheap steel.

Gareth Stace, UK Steel director, said: “This is a stark reminder of how the crisis Britain’s steelmakers are facing is intensifying. Every time someone says prices have bottomed out, they then hit a new low.”