Indian steel industry: Will the alloy brush off its rust?

Naveen Jindal, chairman of Jindal Steel and Power Ltd (JSPL) and a former Congress Party parliamentarian, is an unhappy man. It’s not that he doesn’t appreciate the measures the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government has recently taken to bail out a once-thriving domestic steel industry. He acknowledges the government’s role.

Right from anti-dumping levies to safeguard duties to minimum import price on 66 types of steel products (back in February, the list included as many as 173)—a lot has been done to give some breathing space to the domestic steel makers grappling with cheap imports from China, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, among others.

Jindal’s cause of concern lies elsewhere, though. “Even at the time of Independence, we were making more steel than China. And today, some 70 years later, China is producing 10 times more than what we do. Still, we can increase our capacity by three times in the next 10-15 years if it’s required,” he muses.

What the industry leader does not reveal is perhaps the biggest worry of a country that claims to be the fastest-growing large economy in the world whose gross domestic product (GDP) grew 7.6% in financial year (FY) 2015-16. The anomalies are stark. For one, in spite of the enviable growth numbers, per capita consumption of steel is as low as 60kg compared with the world average of 216kg, and hence a laggard production system that’s lacking China’s drive.

Second, India is known for high-cost steel production. Even in the face of cut-throat global competition, a lean model leading to low cost of production seems a far cry. A case in point being the hot-rolled steel costing around $330 a tonne in China, around $480 a tonne in India and at least $500 per tonne in the US.

However, before announcing the death knell for the steel sector, its legacy may help us understand the situation better.

From smelter to boom

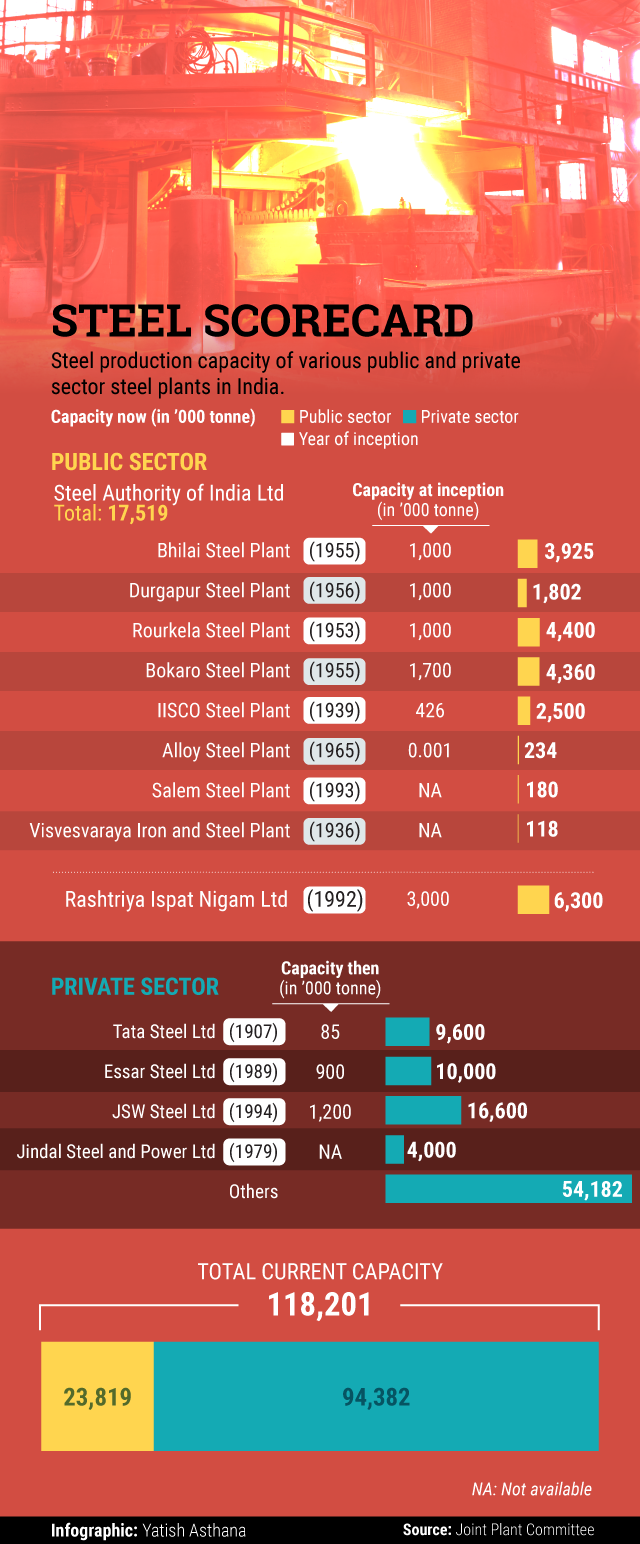

India’s steel industry has come of age since the country’s liberation seven decades ago. Possessing a small but viable steel capacity of around 1.3 million tonnes (MT) per annum at the time of Independence, India overtook the US last year to become the third largest producer of crude steel after China and Japan, according to data compiled by the World Steel Association. The country’s provisional crude steel production capacity stood at 118.20 MT as on 31 March 2016.

As in many sectors, commercial production of iron and steel took off during the pre-Independence era with the Tata group setting up the Tata Iron and Steel Co. Ltd (Tisco) at Sakchi (now Jamshedpur) in 1907. Tisco’s original plant was engineered and constructed with American assistance to produce 35,000 tonnes of pig iron and 50,000 tonnes of saleable steel. Next came the Indian Iron and Steel Co. Ltd (IISCO) in 1918 while Mysore Wood Distillation and Iron Works started operations at the same time. Mild steel production was commenced in the latter in 1936 and the firm’s name was changed to Mysore Iron and Steel Works. It was later rechristened as Visvesvaraya Iron and Steel Ltd, or VISL.

After Independence, the government focused on all core industries, including iron and steel, thus leading to increased public sector investments, enhanced production and new manufacturing units.

In 1953, agreements were signed to set up the first integrated public sector steel plant (with a capacity of 1 MT per annum) at Rourkela in Odisha with collaboration from the erstwhile West Germany. Three years later, two more pacts were signed for setting up steel plants at Bhilai (with assistance from the erstwhile USSR) and Durgapur (with collaboration from the UK) having similar capacity. A new plant at Bokaro, with a capacity of 2.5 MT per annum, went into production in 1973-74 while another facility at Salem in Tamil Nadu went live in 1972. The government also set up Hindustan Steel Ltd (HSL) for the supervision and management of these facilities. Also, with capacity augmentation happening across these plants in phases, the total crude steel production capacity of HSL rose to 3.7 MT in 1968-69 and subsequently to 4 MT in 1972-73.

But there was more in terms of quality and capacity building. India’s first coastal public sector integrated steel plant, Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Ltd, or RINL (also known as Visakhapatnam Steel Plant), came up in August 1992. It had a capacity to produce 3 MT of liquid steel per annum, which is currently being expanded to 6.3 MT per annum.

Keeping in mind the complexity of a fast-expanding infrastructure sector, the then-ministry of steel and mines formed the Steel Authority of India Ltd (SAIL) in 1973 as the holding company to manage the industry. SAIL had an authorised capital of Rs.2,000 crore, and was made responsible for managing the five integrated steel plants at Rourkela, Bhilai, Durgapur, Bokaro and Burnpur, as well as three special plants—Alloy Steels Plant in Durgapur, Salem Steel Plant and VISL. In 1978, SAIL was restructured as an operating company.

According to information available on the website of ministry of steel, during the first two decades of planned economic development—1950-60 and 1960-70—the average annual growth rate of steel production exceeded 8%. But during 1970-80, the growth rate fell to 5.7% per annum and then went up marginally to 6.4% per annum during 1980-90.

With liberalisation came the dismantling of the licensing regime, and iron and steel got taken off the list of industries reserved for state-owned firms. The benefits were many. Compulsory licensing was scrapped, prices were progressively deregulated, foreign investment up to 74% was allowed, and import duty on capital goods was lowered.

This paved the way for private entities finally entering a heavily controlled industry segment. Among these, the most significant are JSW Steel Ltd, Essar Steel Ltd, Jindal Steel and Power Ltd (JSPL), Bhushan Steel Ltd, Electrosteel Steels Ltd (ESL) and Usha Martin Ltd. While the new companies courted cost-effective, state-of-the-art technologies from the very start, the state-run companies opted for modernising and expansion as well.

Beginning 1991-92, production rose from 14.33 MT to 21.4 MT by 1995-96 and to 29.27 MT by 2000-01. Since then, it has been a roller-coaster of sorts, with periodical booms and slumps, but the industry entered a new development stage back in 2007-08, riding high on a resurgent economy and a rising demand for steel.

China and the crisis

Experts have been tom-tomming about how China triggered the steel sector crisis. With its economy slowing down, there has been a dip in overall steel demand, leading to depressed pricing. As its domestic market got flooded with oversupply, China went all out for cheap exports, thus grabbing the largest share of the global market. China is selling below marginal cost and a Bloomberg report, citing Chinese customs data, states that steel exports from China have shot up by 28% to 52.4 MT in the six months to July 2016.

Add to that a large-scale holdback on fixed asset investments across the globe—making up for nearly 80% of global steel demand—and it predicts a bleak time ahead even for global large producers such as Nippon Steel and Sumitomo Metal Corp., JFE Steel Corp., Posco and Hyundai Steel Co. Ltd. These firms are cutting production and reducing price, a move that mercilessly squeezes their margins.

Needless to say, this does not bear good news at home.

According to Indian government data, steel imports rose by 25.6% to 11.71 MT during financial year 2015-16 compared with 9.32 MT in the year-ago period. India was a net importer of the alloy in the last fiscal. On the other hand, India is rapidly losing its export competitiveness, selling just 7.6 MT during the last financial year, which was just a fraction of China’s export of 111.6 MT, as per World Steel Association. Historical data shows that in 2003-04, India’s steel imports were 1.5 MT and exports stood at 4.5 MT. In 2014-15, the country’s steel imports raced to 9.3 MT while exports barely rose to 5.5 MT.

In sync with the depressed domestic and global markets, capacity utilisation fell from 91% in 2010-11 to 77% in 2013-14 (the fall in iron ore production also contributed here), but it is not the only cause for concern. According to the Reserve Bank of India’s Financial Stability Report, “Five out of the top 10 private steel producing companies are under severe stress on account of delayed implementation of their projects due to land acquisition and environmental clearances, among other factors.”

And to top it all, the industry owes around Rs.3 trillion to debt-laden Indian banks, around a tenth of the bad loans, making the sector one of the largest contributors to non-performing assets in the country.

The road ahead

For industry experts and policymakers, the way India’s steel story is unfolding today is quite daunting.

A New Delhi-based macroeconomist, who did not want to be named, blames the earlier culture of protectionism for the so-called death of the leviathan. “The Nehruvian model of development rarely allowed for a market-linked production and costing structure, much like what we are seeing in China today. In the present scenario, the key is to adapt, adapt, adapt and change, keeping in mind your ultimate goal. The government and the industry have to work together to put steel back on track, but a new regime of protectionism won’t do the trick,” the macroeconomist points out.

Even policymakers are aware of that. It’s not surprising, therefore, that the steel ministry has asked the industry to prepare a roadmap for sustainability in the next six months, instead of banking on the trade protections (many of these are World Trade Organization-compliant) the NDA government has doled out so far.

However, an industry executive, who also requested not to be named, believes that the government is now coming up with a bunch of dynamic strategies, designed to trigger consumption-driven growth.

The flagship Make in India campaign is one such move in the right direction, throwing open huge manufacturing possibilities. Of the nearly two dozen focus sectors identified by the government, as many as nine industries—automobile and automobile components, construction, defence manufacturing, electrical machinery, railways, renewable, thermal power, and oil and gas—would depend on large-scale steel buying for the next stage of growth. The government is also talking to infrastructure-related ministries, including railways, shipping and road transport, to ensure increased steel purchase.

It may actually work out.

“Rising domestic demand by sectors such as infrastructure, real estate and automobile can put the Indian steel industry on the world map. Growth in the private sector is expected to be boosted by new policies such as Make in India, import of foreign technology and foreign direct investment,” said Anjani K. Agrawal, national leader, mining and metals sector, at consultancy firm EY.

Jindal of JSPL agrees. “There is a lot of scope still for steel consumption to shore up in this country. People still don’t have pucca housing and a lot of infrastructure needs to be built, railway network needs to be expanded, where steel is the most essential input,” he says.

Interestingly, Narendra Modi’s government seems to be taking a page out of China’s playbook and aims to drive up production in spite of a subdued global market. The government has mooted a perspective plan to boost domestic steel production to 300 MT per annum by 2025 and four mineral-rich states—Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Karnataka—have been identified for setting up of integrated steel plants with collaborations from central and state public sector undertakings via the special purpose vehicle route.

RINL chairman and managing director P. Madhusudan believes this is the road ahead. “Indian steel industry has come a long way and potentials are still very good for the industry. Right now there are many challenges, but these challenges can be overcome. As for low per capita consumption, a lot of initiatives are being taken in terms of building infrastructure, waterways, ports, smart cities and so on. All these augur well for the growth of steel consumption.”

“It’s not a bad strategy on the part of the Modi government,” said the macroeconomist quoted above. “India can actually beat China at its game if it can become the lowest-cost producer of steel with enough to spare for overseas markets. Incidentally, 20% of China’s GDP comes from export and a long-term vision in this respect may augur well for India.”

According to a report by the Working Group on Steel for the 12th Five-Year Plan, there is a potential of raising the per capita steel consumption in the country. These include, among others, an estimated infrastructure investment of nearly a trillion dollar, a projected growth of manufacturing from current 8% to 11-12%, increase in urban population to 600 million by 2030 from the current level of 400 million and emergence of the rural market for steel which currently consumes around 10kg per annum. In addition, schemes such as Bharat Nirman, Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana and rural housing programme can drive consumption.

Agarwal of EY concurs. “With a strong economic outlook and plans to increase steel production, it is likely that India will be on a fast-track growth path and become the second-largest steel producer within a few years,” he adds.